Recently, I looked at the etiquette of mourning in the Victorian and Edwardian period, and the influence of Queen Victoria. This week, I examine alternative approaches to the Victorian funeral.

Queen Victoria was the head of the Church of England until her death in 1901. Thousands of Victorians followed her example after the death of Prince Albert by arranging elaborate Anglican funerals for their loved ones. Although the Church of England was the official religion, according to the Religious Census of 1851, it was not followed by the majority of the population . Non-conformist forms of Christianity were increasingly popular in the latter half of the 19th century and would have a significant impact on the funeral practices of their adherents. In 1851, non-Anglican Christians included Scottish Presbyterians, Independents, Baptists, Society of Friends, Unitarians, Moravians, Wesleyan Methodists, Calvinistic Methodists, Sandemanians, New Church, Brethren, Roman Catholics, Catholic and Apostolic Church, Latter Day Saints, Isolated Congregations and Foreign Churches.

Many of the adherents of these faiths chose to be buried away from parish graveyards and can be found in some of the non-denominational cemeteries in the Deceased Online database. Also in these cemeteries are followers of Judaism, Buddhism, and Islam. Many of the earliest Jewish burials date from the late 19th century when thousands migrated to Britain in the wake of the pogroms in Eastern Europe. I shall be looking further into non-Christian faith burials and cremations in later posts. To find out more about the types of burial records we cover on Deceased Online, take a look at last week's blog post.

The Salvation Army was founded in 1865 and quickly became popular across Britain. When its "Army Mother", Mrs Catherine Booth, died in 1890 she was, of course, given a Salvationist funeral. The Manchester Times (Fri Oct 17, 1890) described the event as "the greatest and most impressive funeral service accorded any woman in modern times." The reporter went on to describe "the vast sea of human faces, many half hidden by the army bonnets, with the red Salvation ribbon, or surmounted by the cap of the cadet or officer". The mourning clothes consisted of "white mourning bands with gold 'S'' on their left arm" and everywhere were decorations such as "draperies, fans, inscriptions".

Mrs Booth's funeral proceedings lasted ten days and were completed at Abney Park Cemetery where her body was taken whilst being followed by a "great procession of Salvationists" who had come from across the country. Each stage in the proceedings was accompanied by several Army bands. Interestingly, those in the procession did not wear crape - the popular material for Victorian mourners - and the reporter noted that Salvationist funeral etiquette did not permit wreaths to be laid on the coffin.

By the 1890s, when high-Victorian funeral etiquette was at its most pervasive, some prominent Britons began to protest at its dominance of national culture. One critic, the artist and philosopher William Morris, insisted on being buried in a plain oak coffin after his death in 1896.

The Church of England also contained many members who detested the extravagance of the contemporary funeral. In 1880 a group of Anglicans came together to form the Church of England Burial, Funeral and Mourning Reform Association. On Saturday 12 October 1889, Jackson's Oxford Journal reported on a speech by the Assocation's honourable secretary, Rev. Frederick Lawrence, who spoke at the city's Corn Exchange the previous Tuesday about the need for burial reform. He complained that the rich were influencing the poor to spend more than they could afford on unnecessary mourning paraphernalia. Instead, Lawrence argued for economy in burial and criticized current funeral practices. There should be, he argued:

Queen Victoria was the head of the Church of England until her death in 1901. Thousands of Victorians followed her example after the death of Prince Albert by arranging elaborate Anglican funerals for their loved ones. Although the Church of England was the official religion, according to the Religious Census of 1851, it was not followed by the majority of the population . Non-conformist forms of Christianity were increasingly popular in the latter half of the 19th century and would have a significant impact on the funeral practices of their adherents. In 1851, non-Anglican Christians included Scottish Presbyterians, Independents, Baptists, Society of Friends, Unitarians, Moravians, Wesleyan Methodists, Calvinistic Methodists, Sandemanians, New Church, Brethren, Roman Catholics, Catholic and Apostolic Church, Latter Day Saints, Isolated Congregations and Foreign Churches.

Many of the adherents of these faiths chose to be buried away from parish graveyards and can be found in some of the non-denominational cemeteries in the Deceased Online database. Also in these cemeteries are followers of Judaism, Buddhism, and Islam. Many of the earliest Jewish burials date from the late 19th century when thousands migrated to Britain in the wake of the pogroms in Eastern Europe. I shall be looking further into non-Christian faith burials and cremations in later posts. To find out more about the types of burial records we cover on Deceased Online, take a look at last week's blog post.

The Salvation Army was founded in 1865 and quickly became popular across Britain. When its "Army Mother", Mrs Catherine Booth, died in 1890 she was, of course, given a Salvationist funeral. The Manchester Times (Fri Oct 17, 1890) described the event as "the greatest and most impressive funeral service accorded any woman in modern times." The reporter went on to describe "the vast sea of human faces, many half hidden by the army bonnets, with the red Salvation ribbon, or surmounted by the cap of the cadet or officer". The mourning clothes consisted of "white mourning bands with gold 'S'' on their left arm" and everywhere were decorations such as "draperies, fans, inscriptions".

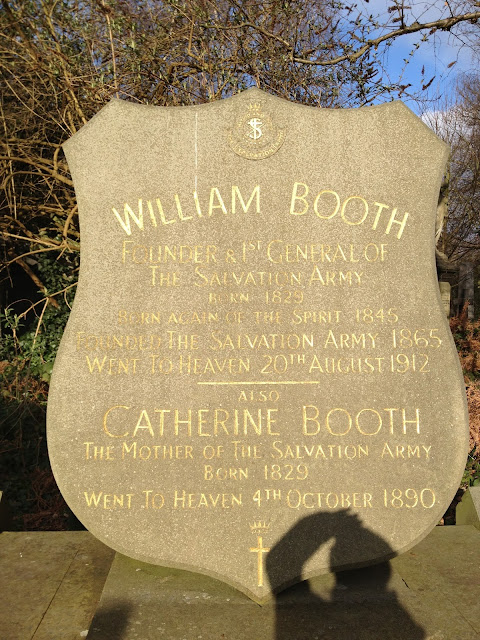

Mrs Booth's funeral proceedings lasted ten days and were completed at Abney Park Cemetery where her body was taken whilst being followed by a "great procession of Salvationists" who had come from across the country. Each stage in the proceedings was accompanied by several Army bands. Interestingly, those in the procession did not wear crape - the popular material for Victorian mourners - and the reporter noted that Salvationist funeral etiquette did not permit wreaths to be laid on the coffin.

| |

| The grave of Catherine Booth (and her husband William) in Abney Park Cemetery, London |

The Church of England also contained many members who detested the extravagance of the contemporary funeral. In 1880 a group of Anglicans came together to form the Church of England Burial, Funeral and Mourning Reform Association. On Saturday 12 October 1889, Jackson's Oxford Journal reported on a speech by the Assocation's honourable secretary, Rev. Frederick Lawrence, who spoke at the city's Corn Exchange the previous Tuesday about the need for burial reform. He complained that the rich were influencing the poor to spend more than they could afford on unnecessary mourning paraphernalia. Instead, Lawrence argued for economy in burial and criticized current funeral practices. There should be, he argued:

. . no special mourning

attire, no crape, no funeral trappings, no costly or durable

coffin, no carriages except for the old and weak, no bricked

grave or vault, no unnecessary show, no feasting, no

treating, no avgoidable exoense. The immediate friends

and neighbours can make the occasion of a death, rather

than a wedding, an opportunity for tendering personal

service, and making useful presents and gifts of money.

The charitable rich can convert their family vaults into

earthen plots, set an example of simplicity and economy

in every details of funeral ceremonial, use floral decoration

sparingly, and make provision of suitable cemeteries a

special object to be aimed at in the near future.

Adherents to certain religious and political views, such as William Morris's Socialism, began to introduce changes in the way they and their family members were buried. Some even gave detailed instructions in their wills. But, the undertakers, crape-sellers and florists of Victorian and Edwardian Britain would see little decrease in their income. It was only with the high casualty rate of the First World War that a visible reduction in mourning etiquette and attire was finally realized. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that not all Victorians wanted elaborate headstone or vaults. Contrary to common belief, the simplicity of a 19th century ancestor's grave may say more about their religious or political beliefs than it does about their financial means.

Comments

Post a Comment